Prof Harold Thimbleby …

Summary

1. Home page

Harold using a ticket machine

— when it takes your cash

it does not confirm the ticket type

Harold Thimbleby is See Change Digital Health Fellow at Swansea University, Wales.

He has just completed an exciting book on digital healthcare, Fix IT (click through to get a summary), which was published October 2021.

His passion is designing dependable systems to accommodate human error, especially in healthcare. See CHI+MED: Multidisciplinary Computer-Human Interaction research for the design and safe use of interactive medical devices for a major project he’s been on. See for some of his recent work in healthcare IT, and for recent coverage in the news.

Harold is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, the Institute of Engineering Technology, the Learned Society of Wales, and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Harold wrote the book Press On, which won the American Publishers’ Association best book award in computer science.

Harold is a visiting professor at UCL and at Middlesex University.

Harold’s web site (this site) is www.harold.thimbleby.net

Harold has been a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit award holder and a Royal Society Leverhulme Trust Senior Research Fellow. He is Emeritus Gresham Professor of Geometry.

Contact

Please email me on harold@thimbleby.netProlific researcher

Harold published his first paper, on menus, in 1978, and has since written many publications: 365 refereed and 676 invited publications, from newspaper articles to articles in Encyclopedia Britannica; he has also given over 527 presentations around the world (as of February 2018). He wrote User Interface Design, published in the ACM Press Frontier Series in 1990, and his fifth book, Press On, was published by MIT Press in 2007, and was 2007 winner of the Association of American Publishers Publishing Awards for Excellence Competition in the Computer and Information Sciences category. He is currently See Change Fellow in Digital Health and has been Royal Society-Leverhulme Trust Senior Research Fellow (2008–2009), Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award Holder (2001–2006). He was awarded the British Computer Society Wilkes Medal, and won a Toshiba Year of Invention prize.

Team builder

Harold founded Swansea University Research Forum, and founded the FIT Lab, 2006. He previously founded University College London Interaction Centre (UCLIC) in 2001.

International reputation

Harold has held visiting positions in Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, etc, and is on numerous international editorial boards and conference committees. He has presented in over 30 different countries. He gave keynotes at the first German Software Ergonomics conference, first International Handheld and Ubiquitous Computing Conference, first Asia-Pacific Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, and many more.

Excellent speaker

Harold is an ACM Distinguished Speaker and has presented over 600 debates, talks, keynotes, workshops and seminars (at Cambridge, MIT, Oxford, Royal Institution, Royal Society, Stanford and the House of Lords, etc). See more …

Advancing public understanding of science

Harold is 28th. Gresham Professor of Geometry, and has been widely interviewed and reported in the media. He had the largest post-bag ever for a New Scientist feature article — about video recorder usability. He has presented at many international science festivals in UK and internationally and at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition.

CV

Harold’s full CV is available in PDF.

2. Tweets

Tweets by haroldthimbleby3. Three passions

My Defender on a submerged, muddy green lane in Brechfa Forest

This sort of road is called a BOAT, a byway open to all traffic, but sometimes a boat would be useful too

1 Work — technology could be safer

Preventable error is blamed for killing many people in hospitals, and some of this is due to poor design of systems, particularly IT systems — whether patient record systems, databases, medical apps or conventional medical devices like infusion pumps, ventilators and glucometers. We’ve been doing a lot of work on making user interfaces to critical systems safer, and this (if any manufacturer or funder was interested!) would start to save lots of lives. Follow this link for more on this or this link for some articles I’ve written. |

| Click to download the full poster |

2 Play — technology is fun

I’ve got a Land Rover Defender (110" TDci SW if you want to know) and have fun using it — it’s a very versatile vehicle. Elsewhere on my web site you can see me giving a lecture with the rear axle of a Defender, so it is serious fun, really!3 Family — technology keeps us in touch

I have a wonderful family. Some of them have neat web sites — check out Prue’s on her work as an artist, and Will’s as a programmer, while Jemima is on pintrest and twitter and Facebook and … Sam and Isaac are probably lurking somewhere on the dark web for all I know. Isaac certainly has a machine-generated web site saying he is doing a PhD.4. Three mysteries and a solution

My letter in The Journal of the Royal Society of Arts (p47, issue 2, 2015)

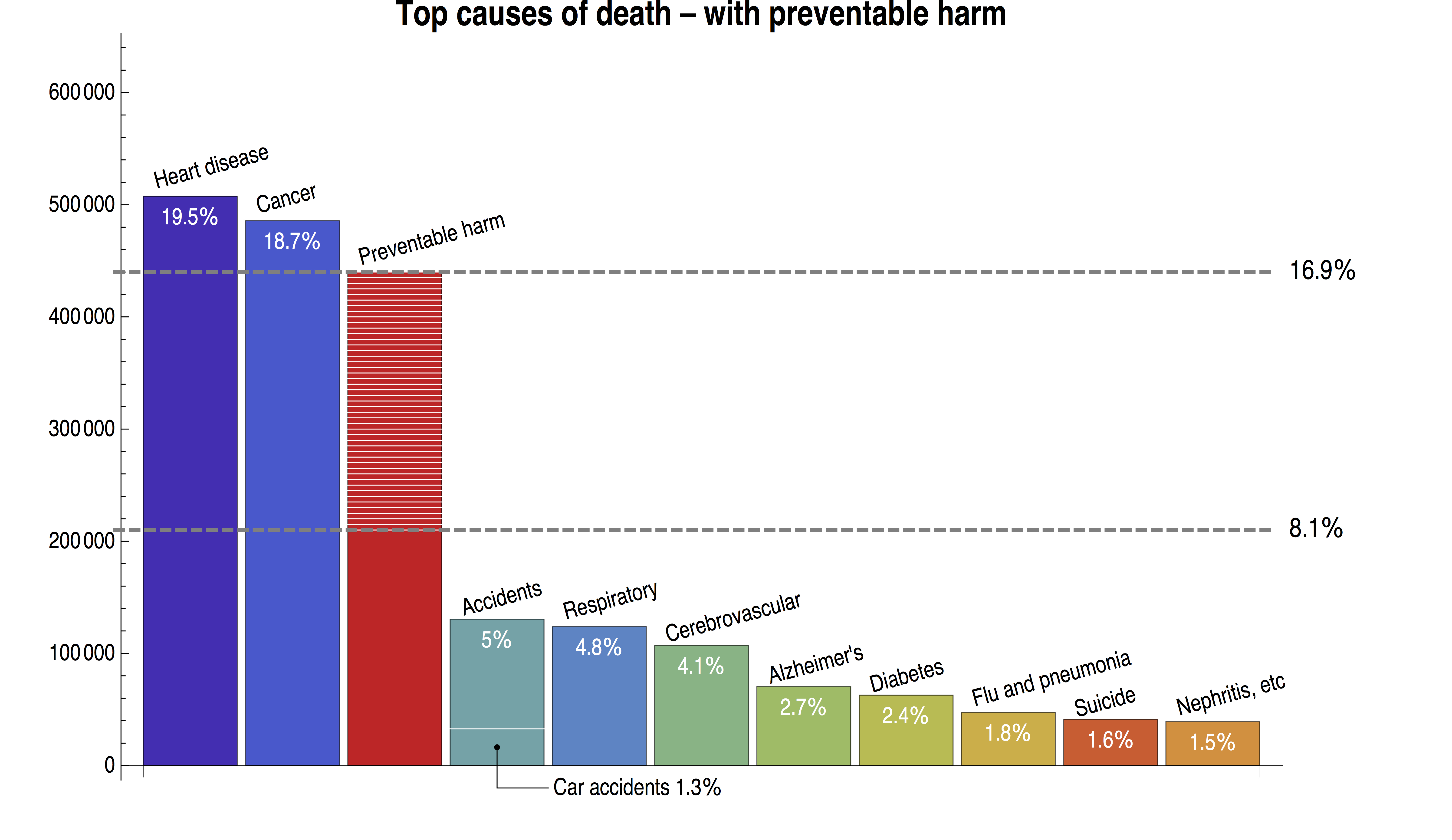

Error in hospitals, if it was considered a disease, would be the third biggest killer after heart disease and cancer. Yet very little is being done about it. Compared to cancer, cybersecurity and big data research it has negligible funding. Why?

Even the lowest estimates put preventable error as a much bigger killer than accidents; healthcare is the most dangerous industry! The higher estimate of error fatalities, 16.9%, is about double the lower estimate I used to make the chart above. Converting the percentages to the UK gives about 41,000 to 87,000 deaths a year (compared to around 2,000 on the roads). Whether you want to argue about details (drop me an email if you do), the figures are tragic.

Some “error deniers” have told me that most people in hospital are going to die anyway. I think that’s like arguing that when a plane crashes most passengers were old people anyway. You can choose to fly or not fly, but few of us have a choice about hospitalisation. Why the persistent denial that it could be so much safer — and a much, much better environment for the people who work there?

It is catastrophic when friends and relatives die. Sometimes, tragically they die as a result of an error, and if there isn’t an honest investigation and more research, more people will die the same way. Yet people donate to cancer research or kidney research, or whatever. Why not (also?) donate to error research? Since so little is spent on error research, every pound donated is going to have far greater leverage saving lives than donating, say, to cancer research where any donation is going to be a very small part of the total budget. I suppose people who die from most diseases have a long time to think about it, but error tends to kill people in minutes? (And very few errors are admitted, whereas it’s hard to deny having cancer.)

Lots of user interfaces have bugs, yet nobody seems interested in fixing them. Bugs kill people, especially in widely used things like calculators which nurses rely on to calculate drug doses. See my poster for some simple examples.

Some “bug deniers” tell me stuff is getting better all the time — and safer. Certainly it is getting more beguiling (even I want a new iPad!). But I haven’t seen good evidence that it’s getting safer; on the contrary it’s getting more complex, harder to use, and filled with more flaws people have to work around (if they notice the flaws, that is; God help us if they don’t).

The best explanation is, I think, attribute substitution: it is very hard to decide what stuff is good (most user interface bugs are invisible to the eye and need serious thought to understand) so we substitute an easier criterion — does it look good. And most new things do look good — otherwise they wouldn’t sell! So our consumer eye is trained to mislead us into buying cute things that are unreliable and unsafe. And since we’ve already decided that the cute things are good, our eyes quickly glaze over when somebody tries to explain the real bugs.

The second-best explanation is cognitive dissonance: you’ve spent a lot of money getting the system, and a lot of time understanding it, so you are going to think it is great. Otherwise you’ll have to admit you wasted all that time, money and effort! Ironically, the worse the system really is, the more the cognitive dissonance will mislead you.

And the solution is…

Here’s a very short animation explaining how to tackle the mysteries and improve the world. Have you got just two and a half minutes to spare?5. News & recent things

A simple example of computer problems in healthcare. The doctor’s name and address are truncated, creating unnecessary ambiguities — but my longer name isn’t trucated!

- Talks at the Danish Week of Health and Innovation, 2019.

- Talk at World Health Organization Global Ministerial Summit on Patient Safety

- Gresham College lecture, Computer Bugs in Hospitals: A New Killer, February 2018. Get the PDF or see it summarised in the news.

- Turning into Effective HCI Researchers & Saving Lives Through Research in Healthcare, Computer Science and HCI — two keynotes at the M-iti Doctoral Symposium 2017, in Funchal, Madeira.

- Keynote “A Crisis To Be Avoided” a human factors workshop for Patient Safety Week at Abertawe Bro Morgannwg NHS University Health Board, 2017.

- Keynote “Human error is not the problem” in Workshop on Interaction in Health Care: Saving lives one interface at a time, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017.

- IT: help or hindrance? talk at the Past, Present and Future of Medicine Society for Acute Medicine and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Conference.

- GE Healthcare Award for Outstanding Impact in Health and Wellbeing, 2014. Awarded to the team in Swansea.

- Improving safety in medical devices and systems — keynote at IEEE Interational Conference on Healthcare Informatics

- The Fitts Law: good style on how to write it, and research using it

- Nomograms, and their use in hospitals

- Safer design movie

- Dance theatre is way better than my interviewed review

- Errors + bugs needn’t mean death (PDF)

- Is IT a dangerous prescription? (PDF)

- Reducing number entry errors: solving a widespread, serious problem (web site)

- Using regular expressions for dependable data entry (web site)

- Interactive medical devices (web site)

- Member of Advocacy Group of the Clinical Human Factors Group.

- Press On

6. Recent papers on healthcare, IT, and medical apps

On this infusion pump, the rate is simultaneously shown as 0.02 mL/h and in an error warning as minus 0.1 (it’s exsanguinating!). What does the log say, and who will be to blame for any harm?

Recent controversies over pandemic modelling

About cybersecurity, including WannaCry

- Lessons From the 100 Nation Ransomware Attack — link to blog with Prof Ross Koppel, University of Pennsylvania

- Cybersecurity problems in a typical hospital (and probably in all of them)

- Safety versus Security in Healthcare IT

General overview

- Improve IT ... improve health

- Trust me I'm a computer

- Preventable error

- Making healthcare safer by understanding, designing and buying better IT

- The Healthtech Declaration

- Improving safety in medical devices and systems

- MediCHI: Safer Interaction in Medical Devices

- Designing IT to reduce drug dose error

Human error

Mostly about apps

- Safety hazards in clinical calculators and apps (poster)

- Safety hazards in clinical calculators and apps (abstract)

- What makes a good clinical app?

- Literature review for apps

- Managing Gravity Infusion Using a Mobile App

- Drug calculations shouldn't be dangerous

Mostly about numbers

- Reasons to Question Seven Segment Displays

- Interactive numerals

- Safer user interfaces: A case study in improving number entry

- Reducing number entry errors: solving a widespread, serious problem

- Unreliable numbers: Error and harm induced by bad design can be reduced by better design

Mostly about infusion pumps

- Analysis of infusion pump error logs and their significance for health care

- Safer "5-key" number entry user interfaces using Differential Formal Analysis

- Issues in number entry user interface styles: Recommendations for mitigation

Other topics

- Understanding User Requirements in Take-Home Diabetes Management Technologies

- Interactive Technologies for Health Special Interest Group

- Ignorance of Interaction Programming Is Killing People

7. Talking & speaking

Lecture at the Royal Institution

Getting to grips with maths using a Land Rover differential

— getting the next generation excited

Harold believes strongly that public understanding and awareness of technology and the science behind it is crucial for us to benefit from it to the full. He has been an ACM Distinguished Speaker.

He gives regular high-level talks on digital healthcare, for instance he gave one at the World Health Organization Global Ministerial Summit on Patient Safety Harold was the keynote speaker at the “Next Generation Tour,” a research workshop that toured New Zealand Universities, inspiring undergraduates to take up research. He regularly runs conferences and workshops. He has given over 80 conference keynotes and over 500 seminars and presentations (including at Cambridge, MIT, Oxford, Royal Institution, Stanford and the House of Lords) in 31 different countries. Harold’s spoken at ten Edinburgh International Science Festivals, the British Association Annual science festival, Spoleto Festival, TECHFEST, Mumbai, Welsh Eisteddfods, and numerous Science Cafés, etc. Harold and Will Thimbleby exhibited an amazing new calculator at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition and at many other exhibitions. Harold has written memorable advice for giving excellent presentations, which he calls Pirate Talks. A selection of recent talks: Computers are involved in all aspects of patient care, from booking appointments through to com- puters in systems that deliver care, such as ventilators, infusion pumps and pacemakers, as well as in computerised decision support systems supporting clinicians. Computers are used in diagnosis and assessment, in MRI scanners, and weighing machines. They control sterlisation, security, and ambulance dispatch. Everybody has mobile phones, email, calculators and medical apps.

It is likely that computer-related preventable error, including cybersecurity exploits, is significant, but more research is needed to quantify its impact. Our own very conservative estimate is that 1,000 deaths per year are caused in the English NHS by unnecessary bugs in computer systems. Regardless of an accurate assessment of numerical impact, though, we should be striving to minimise it, and enabling procurement to choose safer systems. We show that manufacturers appear to be unaware of bugs. If they — the most technical people involved — are unaware of bugs, then neither clinicians nor incident investigators will be properly aware of computer-related causes of patient harm. The aim of this paper is to show that computer-related error is frequently over-looked by programmers and manufacturers. In turn, it is over-looked by regulators, by procurement, and by clinicians. It is ubiquitous and remains highly problematic. We show that there are ways in which computer-related harm can be reduced. We provide 14 specific suggestions for improvement. Improvement will require tighter regulation as well as improved software engineering.

- Keeping patients safe — Trust me I’m a computer?

Computers, IT, digitisation, apps — whatever we call it — is everywhere in healthcare, and it is also racing ahead of healthcare and creating dreams and exciting opportunities for quality improvement and transformation. We want a paperless NHS. Yet we have to be careful what we wish for. We are most familiar with consumer IT, our own personal phones and tablets, but our enthusiasm for this must not be confused with what might be best for healthcare.

This talk has been written up for the Future Hospital Journal

- Turning into Effective HCI Researchers & Saving Lives Through Research in Healthcare, Computer Science and HCI

- Research is a rewarding lifetime career, and arguably the best way to make the world a better place while having fun at the same time. You meet people and make friends all over the world, and governments give you pots of money to do what you want to do. But it is a very competitive world, and to become successful — just even for the first steps of a PhD — means taking research strategy seriously. This talk will help everyone plan their own successful strategies as well as cope with the inevitable failures.

- Healthcare is a surprisingly dangerous place, and it is full of computers. The worldwide fiasco with the WannaCry malware merely made some of the problems very visible. Hospitals stopped working. What else is going wrong? What are the soluble research problems and what can we do about it? The talk is of interest to any computer scientists, HCI and human factors specialists, as well as to clinicians and especially to patients!

- A Crisis To Be Avoided

We want to provide the best patient care, and IT is a large part of that. But as much as IT is exciting, it can also cause serious problems. This interactive workshop concludes with a hands-on review of some of the latest thinking on patient safety.

- Human error is not the problem

Good HCI improves everything, but it has some unspoken assumptions: we need mature HCI and we need market forces to notice and demand good HCI. (That’s why iPhones are so successful.) In healthcare, we need more maturity and more awareness. This talk exposes the problems, and shows how to move healthcare to a more mature view of HCI — which eventually will save many lives.

- IT is the problem with healthcare

It seems obvious that modern healthcare needs more and more modern IT. For instance, it is obvious that most hospitals are years behind patients’ and doctors’ use of apps and social media, and the gap is getting worse. Yet this popular view is fundamentally muddled. In fact IT plays a critical part in hospital inefficiency and avoidable patient harm. Merely having more will be counter-productive. A recent UK court case over the corruption of patient data serves as a good example of our widespread inability to understand, provide, use or develop dependable IT — and we blame the wrong things. This talk will explain key problems with IT and go some way to explaining why hospital error has become Europe’s unacknowledged third biggest killer (close after cancer and heart disease) — and that thinking more clearly about IT is essential. The problems with IT also beset every other organisation, especially public services, including universities, although these organisations rarely kill their customers and students! This talk will be of interest to all thinkers about the future uses of computers, and especially patients, potential patients (that’s all of us), and particularly programmers who could deliver the improved IT that is needed. The talk itself aims to be interesting to general audiences, but experts in formal methods and human factors will recognise the underlying science.

- Human factors failings in the German Enigma design

The German World War II Enigma suffered from design and use weaknesses that facilitated its large-scale decryption first by the Polish and then continued in Britain throughout the war. The main technical weaknesses (self-coding and reciprocal coding) could have been avoided using simple contemporary technology, and therefore the true cause of the weaknesses is not technological but must be sought elsewhere. We will show that human factors issues resulted in the persistent failure to notice and seek out more effective designs. Similar limitations beset the historical literature, which misunderstands the Enigma weaknesses and therefore inhibits broader thinking about design and the critical role of human factors engineering in cryptography.

- Your invitation to fix healthcare IT

After heart disease and cancer, the third most likely cause of death is preventable medical error, and in almost every case IT is involved. Computer scientists should unite in fixing healthcare IT: it requires input from HCI, formal methods, and more, and there is everything to gain. This talk features a wide range of easily avoidable IT problems that have led to unnecessary harm and death.

- IT: help or hindrance?

Healthcare and IT do not fit comfortably together, and there has been a history of visions followed by failure. What is going on behind this, and what do we need to do?

- Creativity, innovation and risk

Encouraging international researchers to consciously think about their research strategy so they are effective and productive in a highly competitive world.

- How to put a winning proposal together

What really matters when you put a winning research proposal together? A stimulating review of the etiquette, assumptions and opportunities. Workshop includes hands-on development and formative review of proposals.

- Human factors and missed solutions to WWII Enigma design weaknesses

“The German World War II Enigma suffered from design weaknesses that facilitated its large-scale decryption by the British throughout the war. The main technical weaknesses (self-coding and reciprocal coding) could have been avoided using simple contemporary technology, and therefore the true cause of the weaknesses is not technological but must be sought elsewhere: we argue that human factors issues resulted in the persistent failure to seek out more effective designs. Similar limitations beset the historical literature, which misunderstands the Enigma weaknesses and therefore inhibits broader thinking about design and the critical role of human factors engineering in cryptography.

Bio: Harold Thimbleby is professor of computer science at Swansea University, Wales, and Emeritus Professor of Geometry, Gresham College, London. He built an electromechanical Enigma in 2002 to illustrate a Gresham College lecture on cryptography, and he has been fascinated by the topic ever since. Harold’s research interest is human error, particularly in complex healthcare systems, but he became interested in the Enigma because its design failures make a provocative analogue to healthcare IT design failures.

- Creativity, innovation and risk in your research

“Most people just ‘do’ research without thinking strategically about their work, their interests and how to do better. What is their plan when a paper or a funding application gets rejected? What is their plan for their plans? How can they be luckier next time? What really matters, and how can we prioritise this to best effect, when all around us are distractions from our priorities?

- Unsafe in any bed

“Unsafe At Any Speed” was the title of Ralph Nader’s damning critique of the 1960s car industry. We are at a similar position with today’s healthcare: Terrible, but quite able to improve. Ross Koppel (University of Pennsylvania, USA) will present examples of Healthcare IT and explore why so much of it fails to respond to the needs of clinicians and patients. Harold Thimbleby will show how many of these problems arise from design failings that remain invisible until it is too late. How can these problems be avoided, so patients are safer? Together Ross and Harold will debate with the audience to respond to ideas for improved healthcare in our increasingly computer-dominated hospitals.

- Unsafe healthcare devices, and how to improve them

“Unsafe At Any Speed was the title of Ralph Nader’s damning critique of the 1960s car industry. We in a very similar position with today’s healthcare: unseen problems with devices and health IT cause and contribute to error. Too often investigations fail to explore the impact of system design on error. To improve, we suggest two obvious ideas: black boxes and a public safety scoring system. Design-induced error needs to be visible to enable learning and finding better solutions to the problem; secondly, safety scores will enable all stakeholders (regulators, procurers, clinicians, incident investigators, journalists, and of course patients) to compare solutions and hence chose better systems.

- Improving safety in medical devices and systems

We need to improve healthcare technologies — electronic patient records, medical devices — by reducing use error and, in particular, unnoticed errors, since unnoticed errors cannot be managed by clinicians to reduce patient harm. Every system we have examined has multiple opportunities for safer design, suggesting a safety scoring system. Making safety scores visible will enable all stakeholders (regulators, procurers, clinicians, incident investigators, journalists, and of course patients) to be better informed, and hence put pressure on manufacturers to improve design safety. In the longer run, safety scores will need to evolve, both to accommodate manufacturers improving device safety and to accommodate insights from further research in design-induced error.

- Human error is not the problem

When something bad happens to a patient, then surely somebody must have done something bad? Although it’s a simple story, it’s usually quite wrong. This talk argues, with lots of surprising examples, that the correct view is you do not want to avoid error — you want to avoid patient harm. Drawing on human factors and computer science, this talk shows the astonishing ways that systems conspire to cause and hide the causes of error. We will then show that better design can reduce harm significantly. We explain why industry is reluctant to improve, and how new policies could help improve technology.

- Social network analysis and interactive device design analysis

All interactive systems respond to what users do by changing what they are doing — though sometimes maybe not in the way you intended! What they were doing before and after any particular user action defines a network. These networks have many interesting properties, which can be readily related to social and other sorts of more familiar networks. For example, hubs are well-connected, and off is usually easy to get to from anywhere, so off is usually — but not always — a hub. It turns out that many interactive systems have quite quirky designs, and network analysis can pinpoint design problems. For example, anaesthetists often switch devices (ventilators etc) off-and-on-again to adjust patient parameters; it turns out that off is often the most between state and therefore usually the best route to get a device to do what you want. It would have been preferable, instead, to design systems so standby was the most between state, as that would allow anaesthetists to adjust some patient values without having to reset all of them, which is what off does. Such design problems may be critical in an operation. In short, this talk will discuss usability problems (particularly medical devices, where design really matters) from the perspective of network analysis.

Mae pob system ryngweithiol yn ymateb i weithredoedd defnyddwyr pan fyddant yn newid yr hyn y maent yn eu wneud — er na fydd hynny bob amser o reidrwydd yn y modd a fwriadwyd gennych! Yr hyn yr oeddent yn ei wneud cyn ac ar ôl unrhyw weithred benodol gan ddefnyddiwr sy’n diffinio rhwydwaith. Mae llawer o nodweddion diddorol i’r rhwydweithiau hyn, a gellir creu cysylltiad hwylus rhyngddynt a rhwydweithiau cymdeithasol a phob math o rwydweithiau eraill mwy cyfarwydd. Er enghraifft, mae digonedd o gysylltiadau i ganolbwyntiau, ac mae fel arfer yn hawdd cyrraedd y cyflwr o fod i ffwrdd (off) o unrhyw le, felly fel arfer — er nad bob amser — canolbwynt yw i ffwrdd. Fel mae’n digwydd, mae dyluniad digon anghyffredin i lawer o systemau rhyngweithiol, ac o ddadansoddi’r rhwydweithiau gellir canfod problemau dylunio. Er enghraifft, bydd anaesthetegwyr yn aml yn troi dyfeisiau (peiriannau anadlu ac ati) i ffwrdd ac ymlaen eto i addasu paramedrau cleifion; fel mae’n digwydd, y cyflwr i ffwrdd yn aml yw’r cyflwr mwyaf rhyngol (between), ac felly fel arfer, dyna’r llwybr gorau i sicrhau bod dyfais yn gwneud yr hyn rydych chi’n ei ddymuno. Buasai’n well dylunio systemau fel mai segur (standby) oedd y cyflwr mwyaf rhyngol, gan y byddai hynny’n golygu bod modd i anaesthetegwyr addasu rhai o werthoedd y claf heb orfod ailosod y cyfan, fel sydd yn digwydd yn achos i ffwrdd. Gall y cyfryw broblemau dylunio fod yn hollbwysig mewn llawdriniaeth. Yn gryno, bydd y sgwrs hon yn trafod problemau hwylustod defnydd (yn arbennig dyfeisiau meddygol, y mae eu dyluniad yn wirioneddol bwysig) o bersbectif dadansoddi rhwydweithiau.

Here’s a selection of other recent talks and lectures:

- Welsh Computer science. Science Advisory Council for Wales

- Improving medicines safety with new technology. Royal Pharmaceutical Society Medicines Safety Symposium

- Widespread errors are fixable by better design. National Biomedical and Clinical Engineering Conference

- Dependable user interfaces — avoiding computer-provoked human error in medical systems. IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems

- Design out harm — don’t design out error. Stanford Research Institute

- Safer Health IT. Aspiring to clinical excellence conference, Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists/UK Clinical Pharmacy Association

- Blindspots and safer medical systems. DesignMed, Stuttgart

- Numbers, numbers everywhere, and none you can trust — not yet! Cardiff Scientific Society

- Secrets of research success. Scottish Informatics and Computer Science Alliance

- Saving lives with science. Royal Society

- Looking beyond human error to its causes. Patient Safety and Clinical Decision Making, Keynote, Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh

- Looking beyond human error to its causes and prevention. Scottish Intensive Care Society Annual Scientific Meeting

- Moving from user interface design to interaction programming. MIT

- Avoiding designed-in errors in interactive medical devices. University of Cambridge

- Thinking out of the Computer Science cargo cult box. Distinguished Lecture Series, St Andrews University

- A new sort of calculator. University of California at Berkeley

- Mud and maths. Royal Institution

- Interaction technology and its impact on science. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA)

- Avoiding death by computer. Swansea Science Café

- School talks …

See also Harold’s views on undergraduate teaching.

He has been widely interviewed and reported in the media. Harold gives numerous public lectures and school talks. He had the largest post-bag ever for a New Scientist feature article he wrote about video recorders.

8. Press On — the book

Press On

Harold Thimbleby, Press On — Principles of Interaction programming, MIT Press, 2007

Winner of the Computer and Information Sciences 2007 award from the Association of American Publishers

Choice Outstanding Academic Title, 2008

Choice is the Association of College & Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association and is the premier source for reviews of academic books, electronic media, and Internet resources of interest to those in higher education; unfortunately you need to register to see details.9. Swansea & the Gower

Rhossili bay

Swansea is right next to the sea, near to the Gower Peninsula, Britain’s first — and finest — area of outstanding natural beauty.

|

|

| Three Cliffs bay 5km from university |

Swansea Bay, looking towards the city 100m from university |

View of Swansea Bay from my office Looking towards Mumbles and Devon |

View of my office (the block in the middle) from my home, on a snowy day |

10. Do research with Harold

The building where we work

If you are interested in doing a PhD (or any other research, such as European Marie Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship) with Harold, please contact me direct; we get zillions of applications, so the best thing to do is engage, visit, and meet us so that we know more about you.

Don’t fill in the University application form first and just wait for things to happen somehow automatically, as perhaps you’ll get lost in the noise!

- If you prepare a PhD proposal on your own, you have three problems: first, is that you will develop it from your undergraduate or masters perspective — but a PhD is very different; secondly, you have made it much harder to find a supervisor who wants to do exactly what you propose. Finally, sending a carefully written research proposal narrows down the people who will be interested in you, and inhibits negotiation.

- A supervisor will be interested in what skills and interests you have, and how good you are. Some supervisors will prefer independent researchers, some will like people they can narrowly supervise to do what they want done. You and your potential supervisor have to negotiate to find out what suits you both.

- For me, the things that get me interested are: you can program (maybe you are good at formal methods too), you are interested in HCI, and you are interested in the things I am interested in. Evidence of those generic skills is much more use than a detailed research proposal.

If you want to do a PhD, you need to find a supervisor who you’ll will be able to enjoy working with for three or four years — and possibly much longer if you follow a research career and carry on collaborating. Find out a bit about potential supervisors (me or my colleagues) and send them crafted emails they will want to read.

I get many spam emails (i.e., that appear to be sent to nobody in particular) from people who want to do their own PhD project, but while this shows you are interested in something (and perhaps how deeply you have thought about it), it shows you aren’t interested in who you will work with.

In reality, you negotiate a project: what can be funded? what is interesting research? what will get a PhD for you? what will work with the team at Swansea? what will Harold be interested in? So, if you are going to email me, make sure I can tell the difference between your email and spam! “Hey Harold, I read your paper … and I want to work with you!” — or something. Also, please send me your CV and any details about funding you have or need — it costs money to live and do a PhD, and that has to be sorted out up front!

If you are at all interested in a research career anywhere — whether as a PhD or as an RA, or even as a PDRF (postdoc) — you should have a good look at Vitae.

Currently, Harold has had excellent postdocs, RAs, PhD researchers, and others:

- Carlos Monroy Aceves

- Chitra Acharya

- Andrea Buck

- Abigail Cauchi

- Jay Doyle

- Andy Gimblett

- Robin Green

- Natalyia Green

- Vicky Hurst

- Howard Ingham

- Alexis Lewis

- Karen Li

- Rhian Morris

- Gerrit Niezen

- Patrick Oladimeji

- Lidia Oshlyansky — now a web consultant

- Tom Owen

- Jen Pearson

- Simon Robinson

- Fern Thomas

- Will Thimbleby — now with Apple, Cupertino

- Huawei Tu

- Victoria Wang

See also SURF, the Swansea University Research Forum, which Harold founded.

11. Examples of research

Working Enigma machine

Harold made for explaining cryptography

Conventional design is often a mix of creativity and evaluation, missing out analytic thinking. This often results in nice-looking systems with problems for their users. Much of Harold’s work has been in working out methods to improve the early stages of design, particularly based on programming, maths or computer science.

Harold has developed many powerful and practical results based on fully working programs and mathematical methods — he is an excellent programmer.

Harold has worked in algorithms, artificial life, autostereograms, computer ethics, computer viruses, digital libraries, human-computer interaction, mobile computing, software engineering and the public understanding of science. Harold is particularly interested in research itself, particularly with the rapid expansion of computer science.

Older things

- Autostereograms (SIRDS)

- Calculators

- Chinese Postman

- Computer algebra

- Cost of knowledge

- Enigma

- Ethics

- Gresham lectures

- Illuminating HCI (light switches)

- LISP and circularity

- Markov modelling

- Matrix modelling

- Press On — Principles of Interaction Programming

- Some school and public talks

- Ticket machine user interfaces

- Warp (explaining programs)

- Weapons of maths construction

12. Funded projects @ Swansea

See EPSRC grants on the web for all Thimbleby’s EPSRC funded projects. (This list doesn’t include travel grants, Fellowships, etc)

| Title | Role | EPSRC reference | fEC value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formally-based tools for user interface analysis and design | PI | EP/F020031 | £711,273.39 |

| FIT Lab/UCLIC PLATFORM: Healthy interactive systems: Resilient, Usable and Appropriate Systems in Healthcare | PI | EP/G003971 | £431,076.07 |

| CHI+MED: Multidisciplinary Computer-Human Interaction research for the design and safe use of interactive medical devices | coI | EP/G059063 | £6,772,571.07 |

| Swansea University :: Bringing People Together | PI | EP/I00145X | £965,708.17 |

| Point of care nanotechnology for early blood clot detection and characterisation in disease screening, theranostic and self monitoring applications | coI | EP/G061882 | £1,078,563.32 |

| The Global Hub in Medical Technologies and NanoHealth at Swansea University | coI | EP/K004549 | £493,092.89 |

| Impact acceleration | coI | EP/K504002 | £637,927.00 |

| Discipline Hopping into Healthcare | PI | EP/L019272 | £96,681.00 |

| The CHERISH-DE Centre — Challenging Human Environments and Research Impact for a Sustainable and Healthy Digital Economy | coI | EP/M022722 | £3,091,610.00 |

13. Teaching

Mobile phones pinned in a butterfly display case

© H Thimbleby, Tippingpoint, Berlin, 2008

Click to see larger image

Seven steps to success?

- Get the generic lecture notes for any module (PDF) — and print them off and use them!

- How to use the lecture notes — instructions for first-timer

- Write your coursework and hand it in (PDF) — advice to writers

- Read my book — if you’re doing a course that needs it

- Read other things, keep up to date, do things, and … start here!

- How to give great presentations (or what to think about during dull presentations)

- Some ideas for projects (though far better to talk to me)

If you are a lecturer or a student who wants to engage with their lecturer, please read Making teaching come alive

And if you want coursework resources for CSM19 (Interactive systems design), click here!

14. Fun and trivia

Trivial Pursuits

My new Apple MacBook Pro 15" laptop keyboard, 9 days out of warranty — it was not out of warranty when it first had the fault, but to diary an appointment at an Apple Store took me just beyond the warranty period.

It has always had a poor keyboard ever since new, and finally one key stopped working altogether, rather than just being unreliable. I made a special trip to Apple, who fixed it. It broke again the next week. Another trip, and Apple repaired it, but this time wanted £481.80. (Actually, £332.50 plus labour plus VAT.)

It’s hard to imagine, for a long-established company, that this isn’t a clever strategy for making money: make an unreliable keyboard (the Apple Store said it was!) and design it so that the keyboard ‘has’ to be replaced along with the entire top of the laptop. Then you can make £481.80 for repairing one key.

I had been thinking of writing a review of USB-C and minidisplay port confusions, and charging confusion, but the key cap failure trumps it.

Front cover of Mathematica Journal based on my program for Genaille’s rods, a fun type of calculator. Henri Genaille’s Rods are a nineteenth-century scheme for doing multiplication, similar to, but easier to use than, the more familiar Napier’s Bones — as you can see, Genaille’s Rods are visually attractive. They are useful in teaching. My article gives full details.

Here’s my name on a card from a Trivial Pursuits game. Mouse over the card to see the answers!

Based on analysis of use of Jonathon Fletcher’s JumpStation, the world’s first web search engine, in fact I said most internet searches were for porn — perhaps not so surprising given the demographic of surfers in those days!

For a more substantial discussion about the internet see my Personal boundaries/global stage article for the IEE 2020 Visions conference, now published in First Monday.

|

|

|

|