Prof Harold Thimbleby …

Three mysteries and a solution

I am developing a new web site for 2024! This old site is just to say something to keep people happy while I work on the new one. Meanwhile, please have a look at our new booklet on patient safety and digital health.

I find the following three things mysterious:

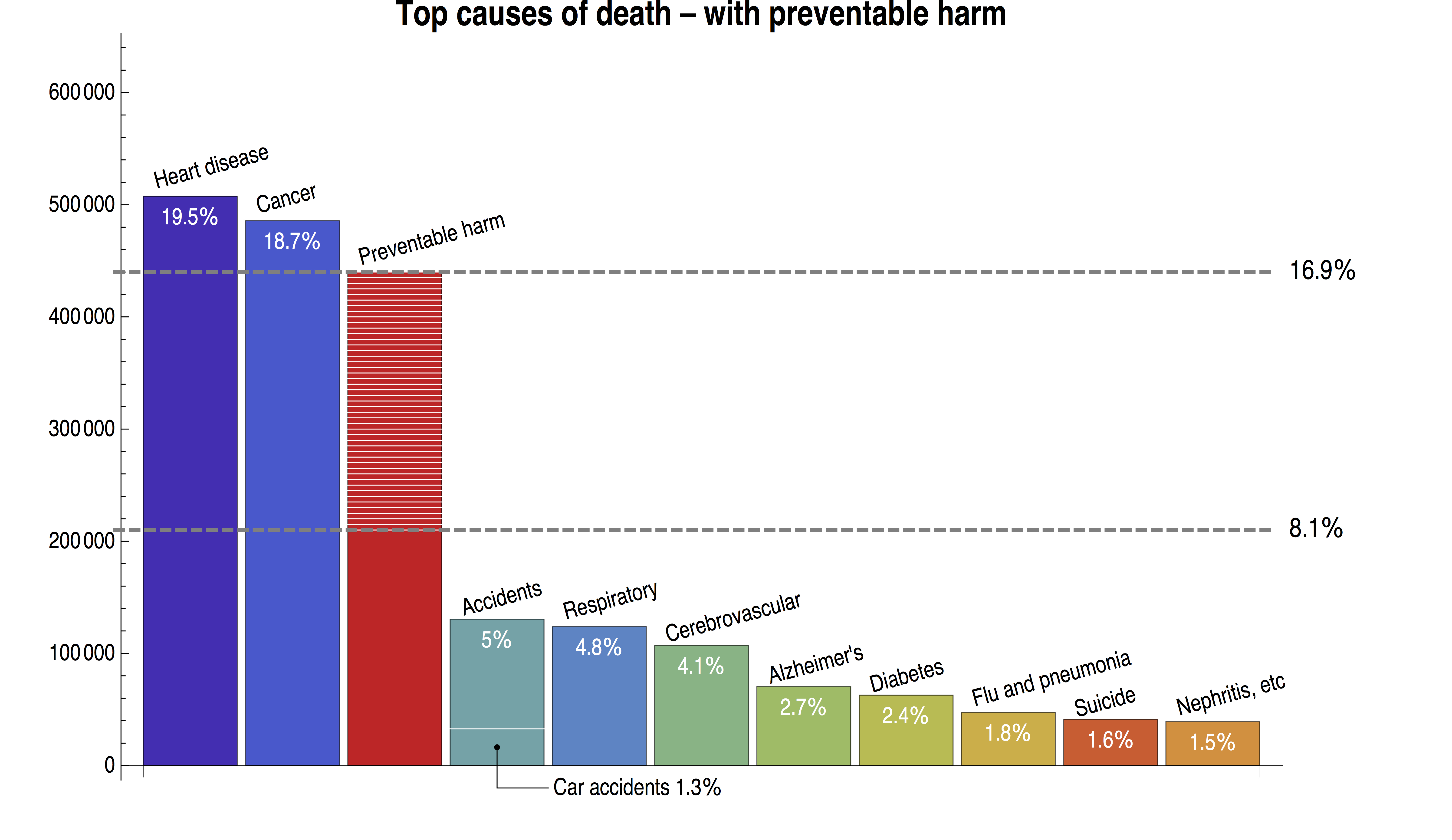

Error in hospitals, if it was considered a disease, would be the third biggest killer after heart disease and cancer. Yet very little is being done about it. Compared to cancer, cybersecurity and big data research it has negligible funding. Why?

Even the lowest estimates put preventable error as a much bigger killer than accidents; healthcare is the most dangerous industry! The higher estimate of error fatalities, 16.9%, is about double the lower estimate I used to make the chart above. Converting the percentages to the UK gives about 41,000 to 87,000 deaths a year (compared to around 2,000 on the roads). Whether you want to argue about details (drop me an email if you do), the figures are tragic.

Some “error deniers” have told me that most people in hospital are going to die anyway. I think that’s like arguing that when a plane crashes most passengers were old people anyway. You can choose to fly or not fly, but few of us have a choice about hospitalisation. Why the persistent denial that it could be so much safer — and a much, much better environment for the people who work there?

It is catastrophic when friends and relatives die. Sometimes, tragically they die as a result of an error, and if there isn’t an honest investigation and more research, more people will die the same way. Yet people donate to cancer research or kidney research, or whatever. Why not (also?) donate to error research? Since so little is spent on error research, every pound donated is going to have far greater leverage saving lives than donating, say, to cancer research where any donation is going to be a very small part of the total budget. I suppose people who die from most diseases have a long time to think about it, but error tends to kill people in minutes? (And very few errors are admitted, whereas it’s hard to deny having cancer.)

Lots of user interfaces have bugs, yet nobody seems interested in fixing them. Bugs kill people, especially in widely used things like calculators which nurses rely on to calculate drug doses. See my poster for some simple examples.

Some “bug deniers” tell me stuff is getting better all the time — and safer. Certainly it is getting more beguiling (even I want a new iPad!). But I haven’t seen good evidence that it’s getting safer; on the contrary it’s getting more complex, harder to use, and filled with more flaws people have to work around (if they notice the flaws, that is; God help us if they don’t).

The best explanation is, I think, attribute substitution: it is very hard to decide what stuff is good (most user interface bugs are invisible to the eye and need serious thought to understand) so we substitute an easier criterion — does it look good. And most new things do look good — otherwise they wouldn’t sell! So our consumer eye is trained to mislead us into buying cute things that are unreliable and unsafe. And since we’ve already decided that the cute things are good, our eyes quickly glaze over when somebody tries to explain the real bugs.

The second-best explanation is cognitive dissonance: you’ve spent a lot of money getting the system, and a lot of time understanding it, so you are going to think it is great. Otherwise you’ll have to admit you wasted all that time, money and effort! Ironically, the worse the system really is, the more the cognitive dissonance will mislead you.

And the solution is…

Here’s a very short animation explaining how to tackle the mysteries and improve the world. Have you got just two and a half minutes to spare?

My letter in The Journal of the Royal Society of Arts (p47, issue 2, 2015)

> Next … News & recent things

|

|

|

|